The one-line answer: SAFe can (and should) reduce overhead if done well.

That’s easy to say but can be tough to implement in existing complex organisational structures. So, in this article we’ll look at how to implement without adding overhead, and where things (often) go wrong…

(for reference: SAFe: Scaled Agile Framework)

For context, this article doesn’t focus on why organisations implement SAFe. However, to cover this briefly, from my experience the most common reasons are to speed up execution or faster time-time-market, or to be more responsive to change. Let’s keep this in mind as we dive further into the topic of reducing overhead, and how shifting the balance from more managers to more doers aligns to achieving these same goals.

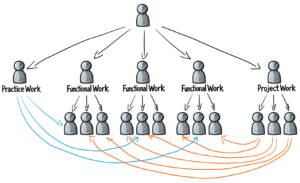

So, what do we have before we start with SAFe? In most organisations, we start with a hierarchy that feeds work down, along with some matrix management in the form of Project Management, and Centres of Practice, also feeding work to the people below.

While a matrix structure became popular a few decades ago, and has persisted in many organisations, it didn’t help the amount that was delivered, or throughput. From my experience once more, in many cases it leads to lower throughput for the size of the organisation. Why? Matrix structures created many funnels for prioritisation, all competing for the same pool of doers.

Enter Scrum and other Agile frameworks (with learning from Lean thinking), promoting the principle that to create speed we need to align the right capacity and skill to the value we’re trying to create, in other words creating cross-functional teams. Agile also promoted incremental build and fast feedback, but I’ll keep focused on structure for this article, with the rationale that without the right structure, practices are limited as to the benefit they can create. So, to get this ‘aligned around value’ structure right, having all the skills and capacity we need in one team, we realised we needed people from different functions.

Many organisations liked the principle of value focused teams and tried to implement this in several ways.

- Some tried restructuring into cross-functional teams. This has some benefits in the alignment of delegation of work to the management structure. However, to implement this requires a major organisational change that can cost many months of slower productivity. Edwards Demming’s observed that changing structure is one of management tools to change the system, with the aim of creating a better system, or maybe one more aligned to the current business demands. However, in today’s rapidly changing environment, can we afford to keep changing structure to keep up? I’d suggest this is difficult and would require reworking many existing supporting organisational processes. What happens when mere months after completing a change we realise that another change is needed? Along with the productivity losses, employees become change fatigued, which leads to many other negative consequences.

- As an alternative, some organisations tried allocating capacity from existing team members to ‘virtual’ Agile teams. This was a good intention but had similar shortfalls to the above image. Leaving people with more than one boss giving them orders each day, left the individual having to make priority calls on their own, often based on who was exerting the most pressure on them, or who paid their bonus. This wasn’t a great recipe for raising overall throughput, or value creation.

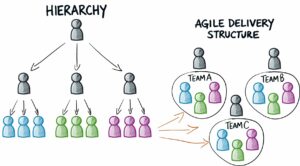

- Then, as a natural next step also advised by many Agile frameworks and aligned to Lean thinking, some organisations was allocating whole people from existing teams to ‘virtual’ Agile teams. Leaving the functional hierarchy intact, and simply managing day-to-day operational capacity through the Agile teams. Our people manage their capacity and work priority through a single funnel, leading to better output. So, this solution is a good one, if you update people performance management to receive input from the Agile structure, to avoid a conflict. And this is what SAFe intends, aligned with the thinking from John Kotter’s dual operating system, so let’s play this one out further.

Leave the hierarchy intact and form a new Agile delivery structure:

The above picture is a simplification, just adding one ‘manager’ role for each team for illustration purposes. I understand that this isn’t a perfect representation of an Agile Team structure, however for now, think of the manager role as a product role helping to prioritise work into self-organising teams and go with me on this. Assuming this simple representation, at first glance, it looks like the structure adds extra managers (and it looks worse if you represent Scrum Masters outside the team of doers). More overhead, a leader’s worst nightmare, a less efficient structure. The teams might be value-aligned, and for this reason we may get quicker, higher quality delivery, but does it have to come at a higher management cost?

Well, not really. Again, in my experience this is where things often go wrong. As before, what should happen, is that when people’s capacity and the day-to-day prioritisation and support of their work shifts from being managed through the hierarchy, to the Agile Delivery Structure. As a consequence, managers will be less busy with trying to manage and direct work and should have capacity to manage some more team members. The shift in manager’s responsibilities is summed up well in Scaled Agile’s new article The Role of People Managers in SAFe.

This change would allow the hierarchy to widen. I say widen here, not flatten, as the latter is not a given. In my experience, hierarchy depth is not necessarily a function of how many people you have, but often a function of decision-making rights and other management controls. However, even if hierarchy levels remain as is, the hierarchy can widen.

In other words, managers, who now have more capacity for people management given they are no longer directing day-to-day work, could take on additional similarly skilled people to manage. This would free up other managers to join the Agile Delivery Structure.

- Managers with a strong people management focus can stay in the hierarchy.

- Managers who are very content focused can move into product focused roles, and managers with strong organisational skills could focus on roles such as Scrum Master or Release Train Engineer.

In the process of Value Stream and ART Identification, a good picture of the delivery focused structure is created. From there it’s up to the implementers or coaches to work with managers who may want to get into the delivery structure, helping them to select the right role, to preserve or even improve that ration of managers to doers.

If we simply create Product Managers and Release Train Engineers from within the teams, we’re not increasing our delivery capacity, we’re possibly reducing it. If managed correctly, this new structure can allow managers to self-select their future role type. It’s important to allow this to happen, and ensure it happens through effective implementation of SAFe coupled with the right leadership support.

Once completed, we are left with a structure that is not only optimised for value delivery, but without extra management overhead. It’s also a structure capable of rapid reorganisation around value, without the overheads of organisational structure change. Or in other words, a structure and practices more capable of dynamically reallocation of resources, which is so necessary to keep up with or stay ahead of the pace of external change. Something about Agility is ringing in my ears…

As a disclaimer as well as an invitation for your own contributions, my views in this article, specifically with regards to how organisations have adopted structure is limited to my experience, and the shared experience of several colleagues, but of course does not cover all angles. So, I’d welcome and look forward to your reflections and input.

0

0